Dr. Pamela Scarborough is currently Director of Public Policy and Education for American Medical Technologies, headquartered in Irvine, California. Her clinical career spans over 35 years, having practiced in a variety of settings including acute, outpatient, home health and long-term care (LTC). Her clinical experience has included traditional physical therapy, orthopedics and sports medicine, cardiac rehabilitation, and wound management. Dr. Scarborough has published book chapters, articles, and monographs on the topics of diabetes and wound care, in addition to being a highly sought-after speaker, invited to present to interdisciplinary audiences at conferences, webinars, and wound management educational activities around the country. She is the founding director of the Wound Certification Prep Course, a nationally recognized wound program to assist in preparing clinicians and wound industry partners for their wound-board certification. She holds an active license as a physical therapist in Texas and is board-certified as a certified wound specialist (CWS). In addition, Dr. Scarborough is certified by the Geriatric Section of the American Physical Therapy Association as a certified exercise expert for aging adults (CEEAA). She has served on numerous symposium planning panels and association boards over her extensive career including the board of the Association for Advanced Wound Care and as an affiliate member of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. She served as the clinical editor for Wound Source, and is on the editorial board of Today’s Wound Clinic. Dr. Scarborough travels extensively teaching and training healthcare providers in wound prevention and management with a focus on the LTC setting. When not traveling she enjoys a quiet, nature-filled life in the Texas Hill Country.

Scarborough_Current Dialogues in Wound Management_2018_Volume 4_Issue 4

Working in or living as a resident in the long-term care (LTC) space can be challenging for clinicians and residents, for different yet overlapping reasons. This healthcare setting is one of the most highly regulated industries in the U.S. LTC clinicians and support staff must thoroughly understand both the clinical approaches to wound prevention and management and the myriad of regulations that drive the clinical, business, and reporting components of this care space.

Wound healing is a complex process requiring interrelated physiological occurrences to take place. The processes for wound healing are aided by effective management of the overall clinical conditions that caused the wound in the first place, or conditions preventing the healing processes from taking place (e.g., diabetes), in addition to a thorough assessment and interventions for the wound bed and surrounding tissues (periwound area). These are two different levels of focus (the whole patient and the wound), both of which are required to create an environment where the patient’s wound(s) can close. Essential to the care of the person with a chronic wound is an accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause of the wound, usually determined by an in-depth patient history and clinical assessment. The duty of diagnosing the etiologies causing the wound(s) is the responsibility of the practitioner (e.g., physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant). Often the facilities staff is focused on the wounds, weekly wound rounds, dressing changes, and documenting tasks in the medical record and needs the practitioner closely involved to take the lead on the medical management for the resident and the issues causing or delaying wound healing. Sometimes facilities have practitioners who can provide this level of evaluation and management, sometimes not, depending on the level of knowledge the practitioner has related to chronic wound healing.

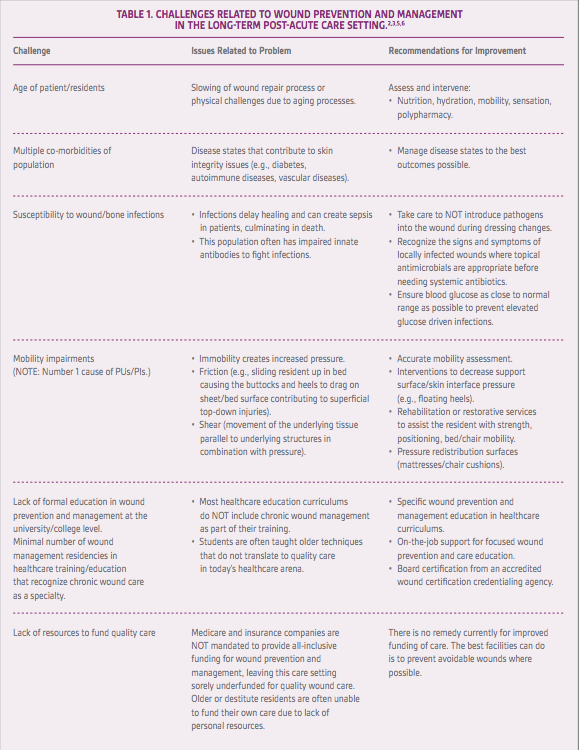

Several patient physiological issues can occur in the LTC setting that impede wound healing. Consider vascularity, for example. On the surface, vascularity is a very simple issue as lack of blood flow results in stalled wound healing. However, getting accurate vascular studies, such as an ankle brachial index, in the LTC environment for lower extremity wounds is often a challenge. Another example of care issues in the LTC is related to reporting and intervening for severely elevated blood glucose. When the directive is given to the nurse from the practitioner to not call them unless the patient’s blood glucose over 300 mg/dL, over 350 mg/dL, even as high as 400 mg/dL, the practitioner may not recognize that severely elevated blood glucose can and does impair wound healing. This is a critical issue in that protein synthesis (required for healing) cannot occur with blood glucose levels this high, and the patient is at risk for wound or other types of infections due to the elevated blood glucose.1Working with the older population, which makes up the largest segment of patients served in LTC, adds another level of challenge for clinical and support teams. These patients often have multiple physiological challenges due to the aging processes, along with co-morbidities and medication all of which often impair the healing processes (Table 1).

An interdisciplinary team approach best serves patients and residents with chronic wounds in all care settings (Figure 1).2 Each team member brings specialized knowledge, skills, and approaches to create the most optimal wound care outcomes for residents during this frequently difficult and complicated process. Team members contribute their specific expertise and collaborate with other team members to interpret findings and develop care plans specific for each patient and their individual issues. The team should negotiate priorities together and agree on a care plan by consensus.2 An important team member is the nursing assistant, who may or may not be trained to recognize skin and wound issues that need to be reported to the supervising nurse. It is worth remembering that the nursing assistant sees the skin of the patients/residents more than anyone else on the team and is an incredibly valuable team member.

Despite the plethora of regulatory guidelines that mandate providing care that meets standard practices for prevention of pressure ulcers/ pressure injuries (PUs/PIs)there are, and will continue to be, PUs/PIs and other chronic wounds in this and all care settings. Some of these wounds are avoidable with appropriate care for prevention, such as most, but not all, PUs/PIs. On the other hand, there are unavoidable PUs/PIs due to multiple challenges for preventing these chronic wounds. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recognizes this and has given the LTC setting what is termed the “unavoidable pressure ulcer/injury (PU/PI)”, also known as the Kennedy Terminal Ulcer or skin failure.3 Each of these terms has overlapping components contributing to the formation of wounds that develop at life’s end or from an unavoidable condition or circumstance.

Some unavoidable PUs/PIs are related to situations that may contribute to PU/PI formation. An example would be a person who is in end-stage congestive heart failure who needs the head of the bed elevated up to 75-80 degrees to drain the lung field fluid (by gravity) to the bottom of the lungs leaving the upper portion free for breathing. The goal is to facilitate the person’s breathing to keep them alive. This is not possible if the bed is flat and the staff is trying to implement a turning schedule to avoid a PU/PI for this resident. Should a PU/PI develop as a result of the required elevation of the head of the bed, the PU/PI would be unavoidable and in keeping with the regulatory mandates. When this situation occurs, it is critical that the practitioner write an order to “keep the head of the bed elevated” at the level needed

Figure 1. Interdisciplinary Wound Management Team. Adapted from Scarborough 2013.2

Figure 1. Interdisciplinary Wound Management Team. Adapted from Scarborough 2013.2

(e.g., 75-80 degrees) to facilitate the patient’s breathing. This order is important for when the surveyor is trying to determine if the facility is to be given a deficiency for the development of a PU/PI.

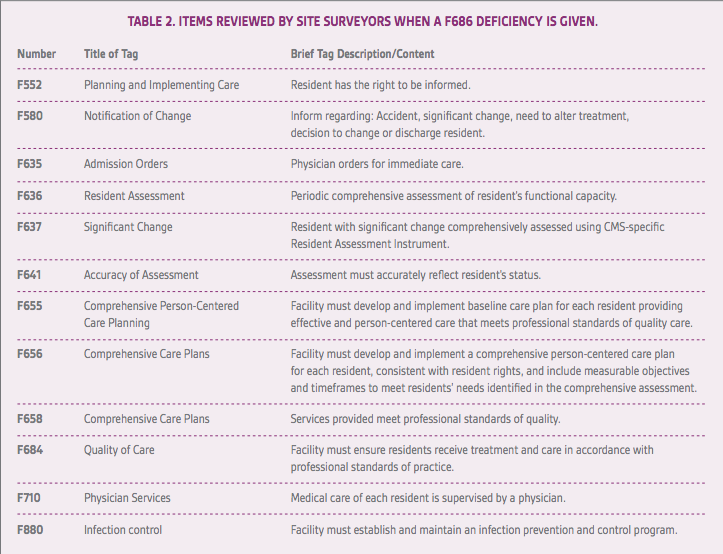

To be successful assessing and managing chronic wounds, it is imperative to incorporate good wound prevention and care interventions that meet today’s standards of practice. In addition to knowing and implemting the standards of wound management, it is critical the clinical and support staff have an understanding of the regulations3 that often describe care recommendations, create coding and reporting mandates, and define how reimbursement is calculated for the LTC industry. In the State Operations Manual,3 the care team needs to read, learn, and implement F686 (Skin Integrity), F684 (Quality of Care), and look at the other F tags that the surveyor is directed to review (Table 2).3 It should be stressed how important the State Operations Manual and Resident Assessment Instrument4documents are for providing wound prevention and care guidance in the LTC care setting. To ignore these documents sets a facility and the staff up for failure, from both clinical and regulatory perspectives, and the resident for less than optimal outcomes from interventions that do not meet current practice standards.The CMS take their PU/PI concepts from the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel’s (NPUAP) clinical practice guideline and have adapted this information to write F686 and F684 sections in the State Operations Manual and the Resident Assessment Instrument, M-Section.5 The guideline from the NPUAP is another document that facilities should have in their library. Current wound textbooks, journals, and in-person and online courses and literature are available, and some of the education is provided at no cost.

Training and educating facility staff in wound prevention and care can help the LTC staff create better outcomes for patients and residents and avoid F-tags and monetary penalties, which can be quite large and detrimental to a facility’s financial health.

References

1.Scarborough P, McGuire J. Diabetes and the diabetic foot. In: Text and atlas of wound diagnosis and treatment. New York, NY: MacGraw Hill Education;2015:99-141.

2.Scarborough, P. Understanding your wound care team: defining unidisciplinary, multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary team models. Kestrel Health Information. http://www.woundsource.com/whitepaper/understanding-your-wound-care-team. Published 2013. Accessed September 2, 2018.

3.State Operations Manual Appendix PP: Guidance to surveyors for long term care. Rev. 173, 11-22-17. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/som107ap_pp_guidelines_ltcf.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2018.

4.Long-term care facility resident assessment instrument 3.0 user’s manual, V1.16. https://downloads.cms.gov/files/1-MDS-30-RAI-Manual-v1-16-October-1-2018.pdf. Published October 2018. Accessed September 2, 2018.

5.National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: clinical practice guideline. Haesler E, ed. Cambridge Media: Perth, Australia; 2014.

6.Ayello, EA, Milne CT, Scarborough P. The Wound Institute Guide to today’s long-term care CMS regulations: a review of the MDS 3.0, Section M, skin conditions and F314 pressure ulcers. The Wound Institute. http://www.TheWoundInstitute.com. Published 2015. Accessed September 2, 2018.