Jean M. de Leon, M.D., is a Professor in UT Southwestern Medical Center’s Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and the Medical Director of the Wound Care & Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Clinic. She specializes in treating complex, chronic, and difficult-to-heal wounds.

Board certified in physical medicine and rehabilitation, Dr. de Leon earned her medical degree at the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine and completed her residency at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. A UT Southwestern faculty member since 2012,

Dr. de Leon has particular and rare expertise in using negative pressure wound therapy for the management of large, complex abdominal wounds with enterocutaneous fistulas. She has developed her own innovative techniques for the management of such wounds and teaches those techniques across the country and internationally.

Leon_Current-Dialogues-in-Wound-Management_2019_Article_3

BACKGROUND TO POST-ACUTE CARE SETTING

Wound care is often discussed in terms of ‘acute’ or ‘chronic’ when assessing outcomes and cost. There is research devoted to evaluating the clinical effectiveness of products as well as the early introduction of various modalities, devices and dressings to maximize the overall healing trajectory and reduce the total cost of healing.

National and international guidelines have also been created for various wound types that define the most appropriate evidence-based assessment and processes for care. These guidelines and randomized trials evaluating treatment strategies, however, do not discuss environments of care and how the setting impacts strategies and outcomes.

Current episode-based payment models push healthcare systems to manage care beyond the short-term acute care hospital stay. Quality measures that evaluate the return to acute (RTA) rate or cost-of-care 30 days post-discharge are driving more coordination of care as well as partnerships with facilities outside the short-term acute care hospital. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) were introduced in 2011 to increase care coordination, and subsequently reduce unnecessary medical care and improve health outcomes. Medicare’s largest ACO model, the Shared Savings Program (MSSP) found that the largest single contributor to savings was in reductions in the Post-Acute Care (PAC) setting.1 Additionally, a study that compared traditional Medicare beneficiaries to Medicare advantage beneficiaries revealed the largest variation in spending and utilization occurred in the area of post-acute care. The Medicare Advantage beneficiaries used less post-acute care services and incurred less cost.2

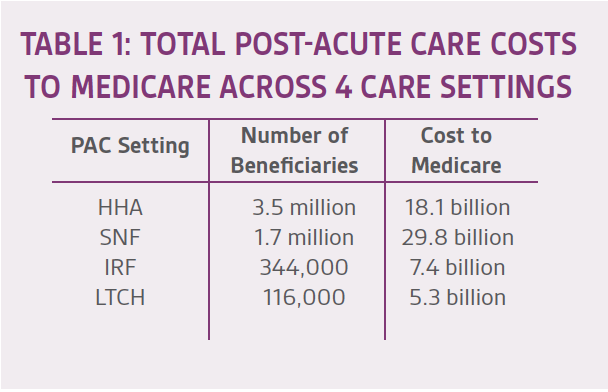

In 2014, the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act (IMPACT Act) was implemented and requires post-acute care standardized patient assessment data to be collected. The intent is to improve quality and cost of care through standardization of data elements in the post-acute care setting. Healthcare systems, ACOs and Medicare are highly focused on post-acute care because of the large expenditures associated with this care setting (Table 1). About 40% of Medicare acute inpatient hospital discharges result in the use of PAC3 through four main settings : Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs); home health agencies (HHAs); inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs); and long-term acute care hospitals (LTCHs). In 2015, Medicare spending on PAC services totaled $60 billion.4

A retrospective review of SNF utilization in MSSP ACO’s between 2009 and 2014 noted “the rapid growth in post-acute spending has been driven by increasing use of care in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), which are the most common type of post-acute facility used and are reimbursed by Medicare on a per diem basis”.5 In addition, the study concluded that the reduction in expenditure was mainly influenced by clinical decision making both within the hospital and post-acute setting rather than the implementation of hospital-wide initiatives, or the use of a preferred SNF network.5

There is significant variation in the supply and the use of PAC providers across the country. This has contributed to the variability in PAC costs. More importantly, there is a lack of data regarding the impact of PAC on patient outcomes. Which PAC setting is best for each patient? At what point across the patient’s continuum of care should they transition to post-acute care and for how long?

WOUND CARE PATIENTS IN THE POST-ACUTE SETTING:

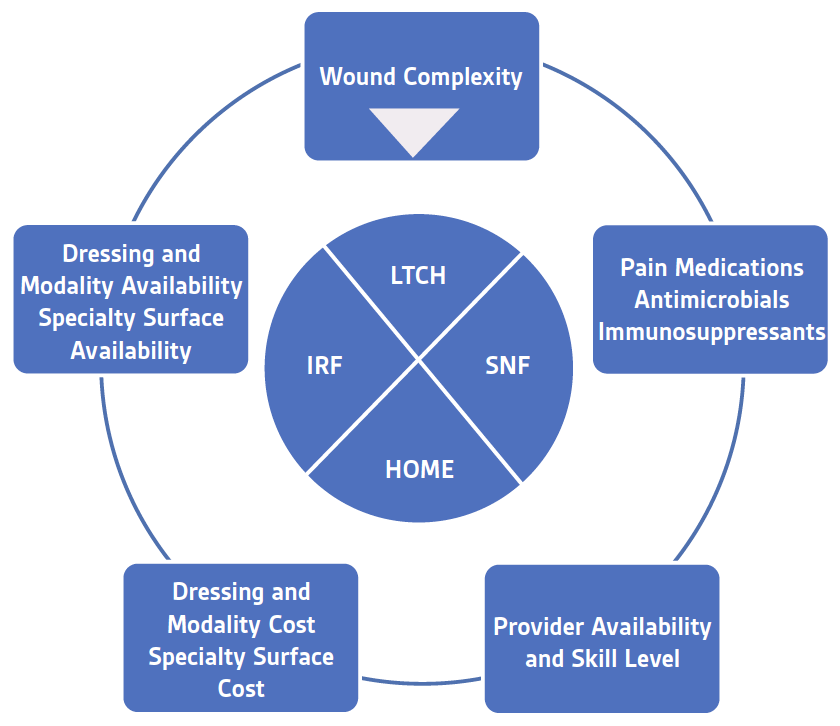

The timing of transition and choice of PAC setting for patients with wound care needs is often dictated not only by wound characteristics but also by resource needs. For instance, a patient on negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in the acute short stay hospital may be discharged to their home with home health care, to a skilled nursing facility, to an inpatient rehabilitation facility, or to a long-term care hospital with NPWT. The decision is not based on just having NPWT and is multi-factorial.

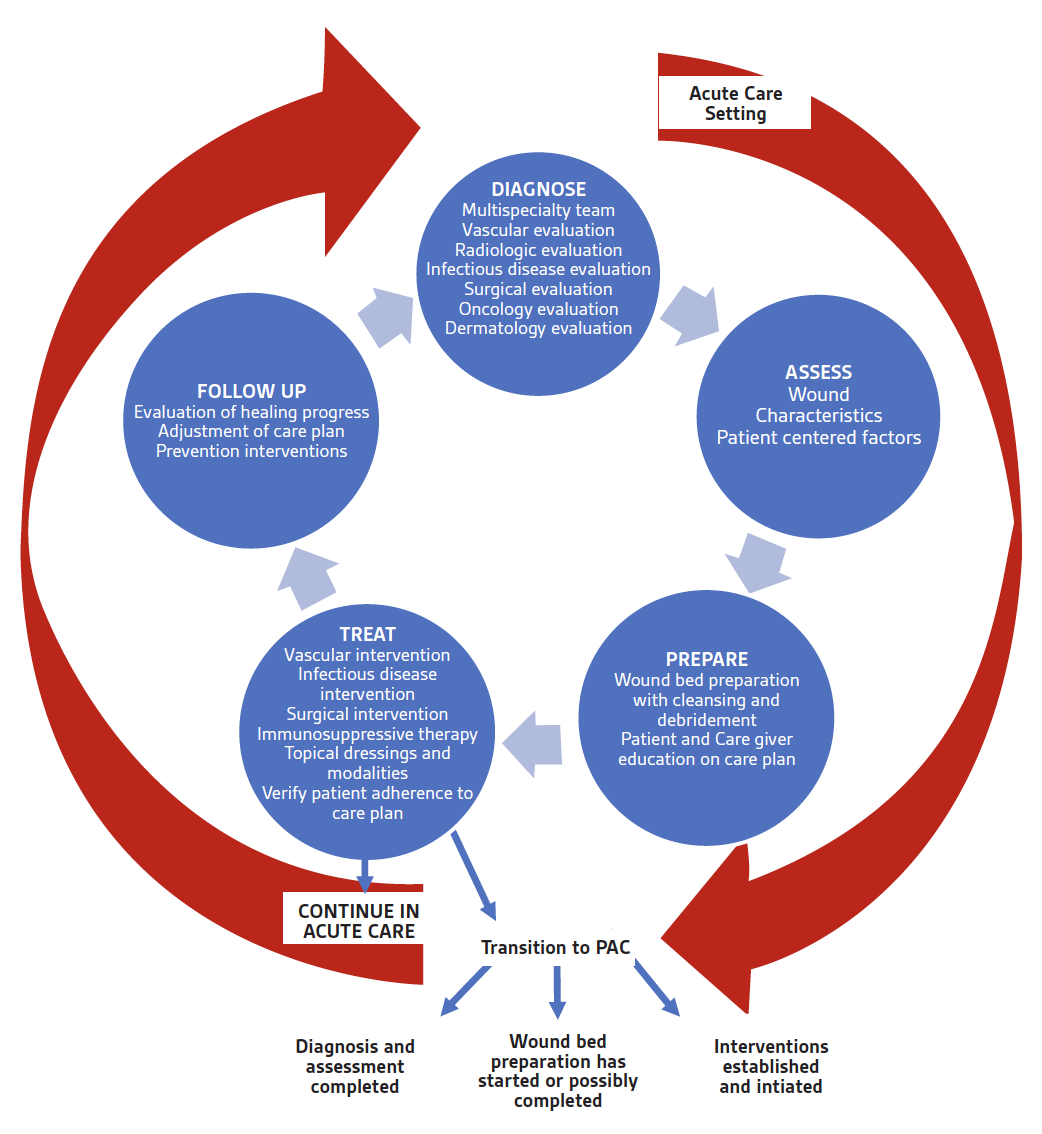

Consider a wound care resource decision matrix that considers wound complexity. Start with a generally accepted strategy for wound care management and consider what resources are needed at each step. Ideally a patient-centered treatment plan is established before any transition to PAC. Of course, if the treatment plan is not finalized or has been evolving due to complications in healing, then the care would be continued in the acute care setting. Once the plan has stabilized, choosing which location to transition the care plan to involves a detailed assessment of the current resources needed and reevaluation of the need to continue each of the resources (Figures 1-2).

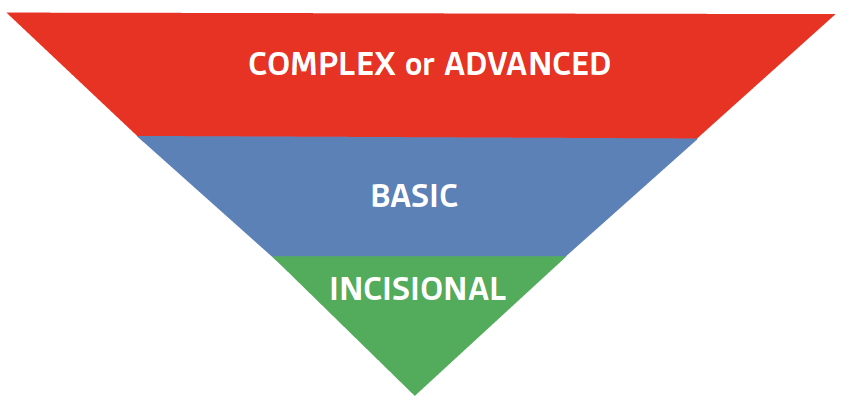

With topical dressings such as contact layers, collagens, alginates, hydrofibers, antimicrobials, and foams there is consideration given to the cost of the dressings as well as the availability of each of the dressings in the various settings. Additionally, the management of pain associated with the dressing change impacts the level of care. Use of intravenous (IV) medications for pain or treatment of a deep structure infection or immunosuppression, for instance, may drastically limit the choice of PAC setting. Consider wound complexity as having 3 levels (Figure 3).

Incisional care can be accomplished with several products, often dictated by the provider and the setting. Incisional NPWT utilizing the PREVENA™ Incision Management System is applied in the operating room. It may be changed by the surgeons on the floor once before discharge from the short-term acute setting, but it is not changed in any of the post-acute settings except for potentially outpatient surgical or wound clinics. In part, this is due to the fact that the incisions remain closed after 1 application (7 days). The PREVENA™ System device/dressing is disposable and can be expensive to stock in settings other than the acute hospital.

Non-complex wounds may require NPWT utilizing devices such as the ACTIV.A.C.™ Therapy System, V.A.C. FREEDOM™ Therapy System, V.A.C.VIA™ Therapy system or other such devices. Application of these devices can be done in acute care hospitals, long-term acute hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, home, and outpatient settings. General guidelines for wound care use of NPWT would be

- a readily visualized wound base without tunneling, undermining, or exposed fragile structures in a location that can be readily sealed under negative pressure

Typically, these set ups can be accomplished by a single provider with the use of no pain medication or an oral pain medication. Foam dressings include either V.A.C. WHITEFOAM™ Dressings, V.A.C.® GRANUFOAM™ Dressings, or V.A.C.® GRANUFOAM SILVER™ Dressings. In the acute care hospital or LTCH, additional NPWT foam dressing options include V.A.C. VERAFLO™ Dressings. The choice of foam is clinically driven by the characteristics of the wound such as occurrence of slough, type of wound exudate, exposed structures such as bone or bowel, and presence of positive tissue cultures.

A complex or advanced wound would be characterized by a wound with tunnels, undermining and/or exposed structures that require tailored packing and/or additional products such as contact layers. Pain medication needs may be intravenous. Timed wound instillation of solutions through V.A.C. VERAFLO™ Therapy with any combination of foams is often limited to acute care hospitals and some LTCH hospitals and few SNFs. Instillation therapy is often chosen for wounds with exposed structures at risk for deep infections or those with tissue already cultured positive. It is important to note that exposed structures such as vessels, organs, and nerves need to be protected with non-adherent dressings prior to the application of foam dressings. Additionally, V.A.C. VERAFLO™ Therapy with V.A.C. VERAFLO CLEANSE CHOICE™ Dressings may be the selected form of wound cleansing especially in patients who are not currently candidates for surgical debridement.

A complex or advanced set up may also be considered in any clinical situation that requires a prolonged NPWT placement time due to

- the number or size of the wounds

- the need for additional providers to assist in the placement

- excessive bleeding or hemostasis issues

- association with enterocutaneous fistulas within the wound

Although many wound set ups may be advanced within the acute care hospital where there are more resources and experienced providers, there may be an opportunity to tailor a more basic set up for continuation of progress in a post-acute care setting with more limited resources. It should not be assumed that the current acute care hospital set up must be carried forward into the post-acute care setting. The clinical goal of the acute setting should be to temporize the wound in the most critical time period and establish a strategy for continued progress. When considering which post-acute care setting is appropriate based on wound care needs solely, any wound that can be cared for at home or in a clinic setting can also be cared for in a SNF setting. Few wound care plans require an LTCH setting but the complexity of other medical conditions, the need for expensive medications, or the need for IV pain medication may result in wound patients of all levels entering an LTCH setting.

It should be noted that provider skill in each setting may vary from having a wound care physician who follows regularly to no physician oversight within the facility except by the admitting primary care physician. Reassessment of the patient at each transition point can help keep the overall care plan patient-centered and may reduce unnecessary expenditure.

CASE EXAMPLES:

CASE 1: A 45-year-old female with paraplegia was admitted for suspected infection, and a noted worsening pressure ulcer to her sacral area. She was initially started on IV antibiotics and V.A.C. VERAFLO™ Therapy with hypochlorous acid solution using the V.A.C. VERAFLO CLEANSE CHOICE™ Dressing. She was placed on a pressure redistribution surface. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed no evidence of osteomyelitis. The acute care hospital was ready to transition the patient to PAC. If they had considered her current regimen, she would have needed a transition to a LTCH for V.A.C. VERAFLO™ Therapy application and IV antibiotics. If, however, the wound was reevaluated and noted to have a clean granulated base, the antibiotics were changed to oral dose or discontinued, and V.A.C. VERAFLO™ Therapy switched to traditional NPWT, then the patient could have been transitioned back to home with home health care. The patient could have also transitioned to a SNF if social factors that lead to the worsening of the ulcer in the home setting were present.

Surgical wound closure may have also been a treatment option that would have influenced the patient’s transition to post-acute care. If the patient had undergone a myocutaneous flap closure and required an air fluidized surface, then the cost and availability may have limited the patient’s transition to a LTCH and one of a few skilled nursing facilities.

CASE 2: A 72-year-old male with a history of diabetes and a non-healing ulcer of the right foot was admitted to the acute care hospital and diagnosed with osteomyelitis and arterial disease. He underwent a right lower extremity bypass to increase blood flow to the area and ultimately underwent a right transmetatarsal amputation. Immediately after the procedure, the patient was treated with PREVENA™ Incision Management System. The acute care hospital was ready to transition the patient to PAC. With this in mind, the PREVENA™ System was removed, and the incision remained intact without evidence of infection. The patient was changed to a topical dressing of xeroform gauze and an absorbent secondary dressing. Minimal pain complaints were made during dressing changes owing to optimal pain management with oral medication. The patient required four more weeks of intravenous antibiotics. The PAC setting for this patient was dictated by the final choice of antibiotics.

SUMMARY

Current payment models are focused on coordination of care across the entire care continuum. Understanding the resources involved in the care of patients with wounds, as well as an awareness of what resources can be provided in each PAC setting may provide a more patient-centered strategy and more efficient care. Additionally, utilizing a set of standardized quality measures across all settings will provide more data on the best use of post-acute care that will guide future treatment and care management decisions. Unfortunately, any decision matrix that promotes transition choices to the least costly setting may not ensure optimal clinical outcomes. Further study of both cost and clinical outcomes is required to further understand this important issue.

References

- McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Early performance of accountable care organizations in Medicare. N Engl J Med 2016;374(24):2357-66.

- Curto V, Einav L, Finkelstein A, Levin JD, Bhattacharya J. Heathcare spending and utilization in public and private Medicare. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2017.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Encouraging medicare beneficiaries to use higher quality post-acute care providers. In Report to the congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Washington, DC; Published June 2018;111-126.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Implementing a unified payment system for post-acute care. In Report to the congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Washington, DC; Published June 2017;3-25.

- McWilliams JM, Glistrap LG, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC. Changes in Postacute Care in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):518-526.

NOTE: As with any case study, the results and outcomes should not be interpreted as a guarantee or warranty of similar results. Individual results may vary depending on the patient’s circumstances and condition.

Specific indications, contraindications, warnings, precautions and safety information exist for KCI products and therapies. Please consult a clinician and production instructions for use prior to applications. This material is intended for healthcare professionals.